- Dissecting the Markets

- Posts

- Your Coffee Habit Is Building the Economy (And Your Childhood Is Still Controlling Your Wallet)

Your Coffee Habit Is Building the Economy (And Your Childhood Is Still Controlling Your Wallet)

Why the most powerful economic forces aren't found in boardrooms or stock markets, but in our daily routines and deepest memories

Happy Monday!

Throughout last week, I dove deep into the Klarna S-1 and published an essay on my bull thesis exclusively on $KLAR ( ▼ 0.96% ) on Yahoo Finance Community. You can read the essay here.

Instead of writing an essay on why I’m bullish on a certain stock or dive deep into the ROI of a company’s new product/service/acquisition, I’ve decided to write two mini essays on observations I’ve had on personal finance and macroeconomics. These essays are The Economy of Habit and The Echo Chamber of Childhood Dreams.

Enjoy these essays! And don’t forget to subscribe :)

The Economy of Habit

What if the most powerful force in the modern economy wasn’t a grand, heroic gesture but a quiet, daily ritual? We often imagine economic growth as a series of market crashes and soaring stock charts, international trade deals, or the rise of monumental technologies. But the truth is far more intimate and subtle. The engine of prosperity is not fueled by singular, bold actions; it is built, block by block, from the mundane, quiet habits of billions of people. It is the entrepreneur who holds the profound insight to see this and to harness it.

A man in a suit is guiding both construction workers and robots in building a mall in Cebu. Made with ImageFX.

Entrepreneurs are not merely inventors of new products; they are architects of human behavior. Their genius lies in observing what people already do on a daily basis and designing a system that turns those routines into economic value. Consider the simple act of grabbing a coffee before work. To an individual, this is a personal ritual, a small moment of indulgence to kickstart the day. But to a company like Starbucks, it is the anchor of a global logistics network.

The simple habit of walking into a café and ordering a latte is the fuel that powers a multi-billion-dollar enterprise, employing thousands of baristas, farmers, and supply chain managers. The customer is a participant in a vast, unseen economic dance, and they don't even need to be aware of the choreography to perform their part perfectly.

This principle extends to the very heart of innovation. The world’s most transformative companies are built on the aggregation of seemingly insignificant tasks. At companies like Tesla or Apple, the vision is to build an electric car or a new kind of smartphone. The day-to-day reality, however, is a team of engineers working on a single line of code, a designer refining a small curve on a chassis, or a data analyst optimizing a single algorithm.

None of these individual tasks feels earth-shattering in the moment. Yet, when stacked one upon another, they culminate in a finished product that reshapes entire industries. The daily habits of dedicated employees are the little steps that build great things—the quiet, diligent work that turns a big idea into a tangible reality.

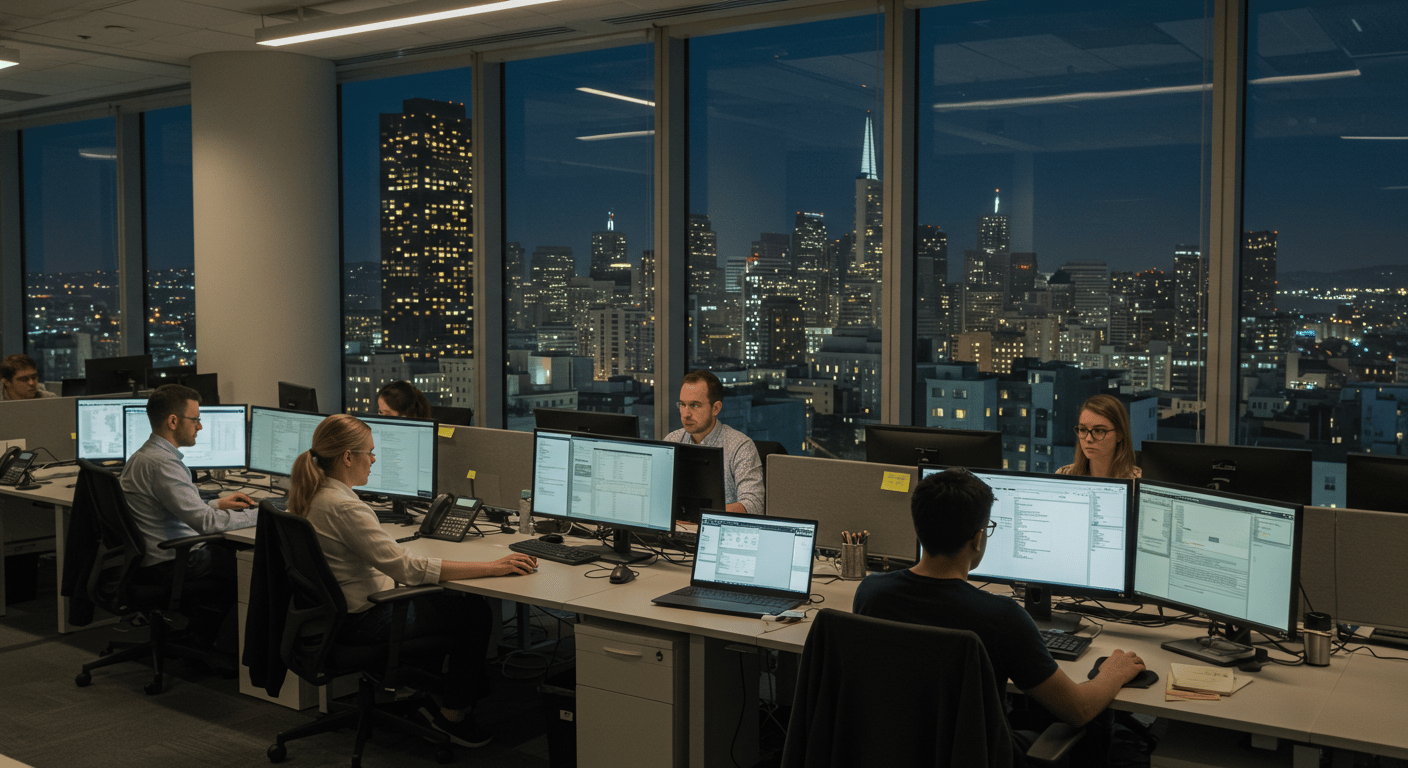

Office workers working late at night in a skyscraper office. The windows show a nice view of downtown SF. Made with ImageFX.

This relationship between habit and value isn't limited to the production side of the equation. In fact, the most transformative economic insights have come from understanding how the habits of production can be directly linked to the habits of consumption. This is precisely the insight that led to one of the most significant economic shifts in modern history.

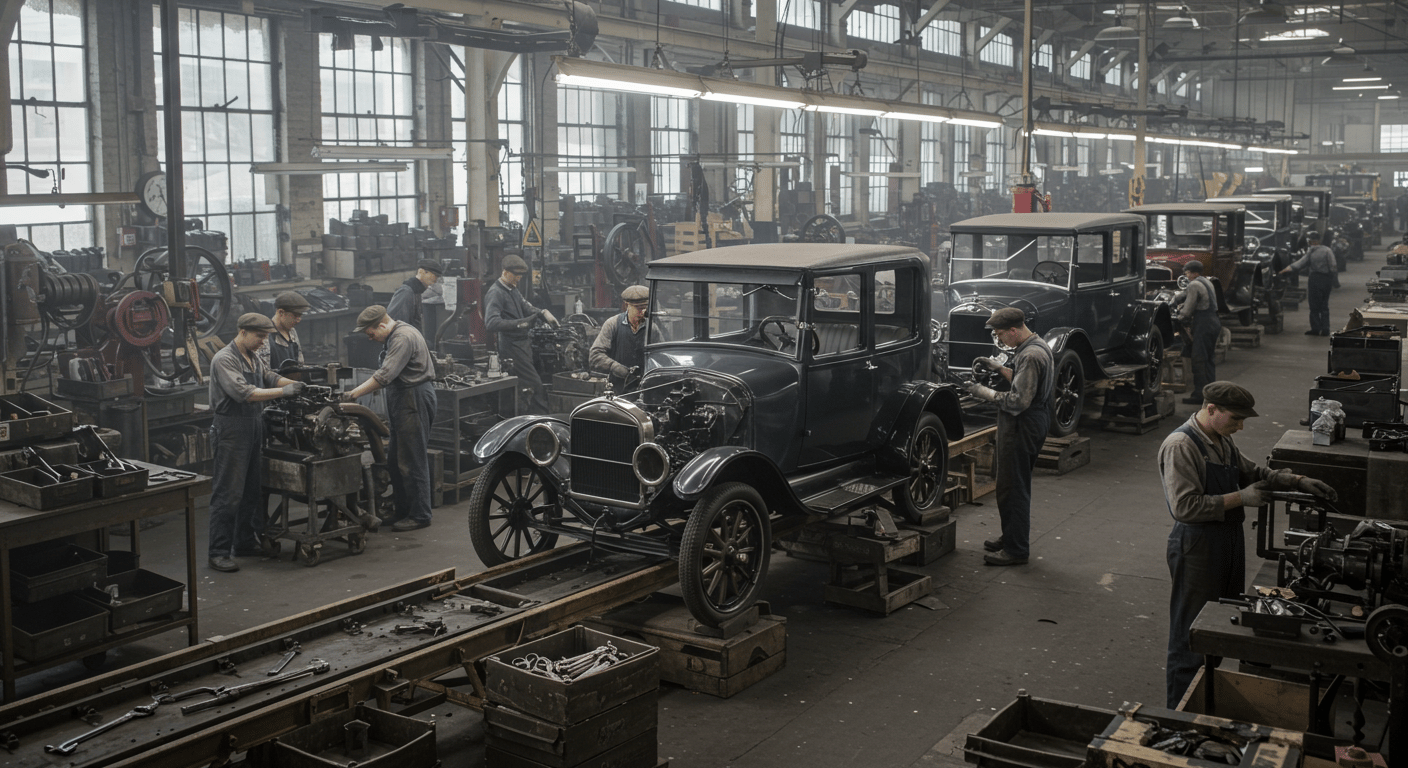

In 1914, Henry Ford made the radical decision to raise the daily wage for his factory workers to five dollars, more than doubling their previous pay. This move seemed counterintuitive to his competitors, but Ford understood a deeper truth: by paying his workers a living wage, he was turning them into consumers. He created a market for the very cars they were building.

The daily habit of going to work and earning a higher wage was translated into the habit of purchasing goods, which in turn fueled the demand for more cars and allowed Ford to grow its production even further. This strategic decision was a critical step in building the American middle class, proving that an entrepreneur's ability to create a product is only as powerful as their ability to create a consumer base for it.

Yet, a century after Ford’s profound insight, we are witnessing a curious and subtle retreat from this very model. Instead of building products and services for the masses, many of the world’s most iconic companies—from Disney to Delta to General Motors—are increasingly focused on catering to the top 10 percent. They are raising prices and prioritizing premium experiences, effectively pricing the rest of the population out of things that were once accessible.

While this strategy may lead to higher profit margins in the short term, it represents a profound retreat from the core economic principle that fueled an era of unprecedented prosperity. When a company abandons the mass market, it sacrifices the very engine of broad-based consumption that drives a healthy, growing economy. The modest profit gains from catering to a few are far outweighed by the lost opportunity to ignite the consumption habits of millions.

Workers building Model T's in the 1920s in a factory. Made with ImageFX.

This lens of understanding offers a powerful new perspective, particularly for emerging economies. For too long, we have viewed economic development as something that must be built from the top down, with large-scale projects and government-led initiatives. But what if the true catalyst for prosperity is the humble act of consumption?

When individuals in an emerging economy begin to have the means to buy a new product—be it a smartphone, a reliable refrigerator, or a better cup of coffee—they are not just satisfying a want. They are igniting a chain reaction of economic activity. Their purchases fuel the production lines that employ their neighbors, create demand for local suppliers, and generate the tax revenue that builds infrastructure.

Their consumption is not a sign of excess; it is the vital heartbeat that fuels a larger, healthier economy, leading to a higher standard of living and more economic opportunities for everyone.

The profound insight is that a powerful economy is an organic phenomenon, growing from the ground up, one habit at a time. It is a testament to the power of human collaboration and the genius of the entrepreneur who can harness our shared routines.

The next time you perform a simple daily task—checking a social media feed, taking an Uber, or ordering a coffee—consider the quiet magic at play. You aren’t just living your life; you are participating in the constant, dynamic construction of the world around you.

The Echo Chamber of Childhood Dreams

Have you ever seen an adult buy something like a vintage toy, a trip to a theme park, or a rare collectible, and wondered what’s really going on? At first glance, it might just look like an impulse purchase. But if you look closer, you'll see something far more interesting: a conversation between who we are now and who we used to be. It's a pattern that runs deeper than simple consumerism, tapping into the unwritten scripts of our childhoods.

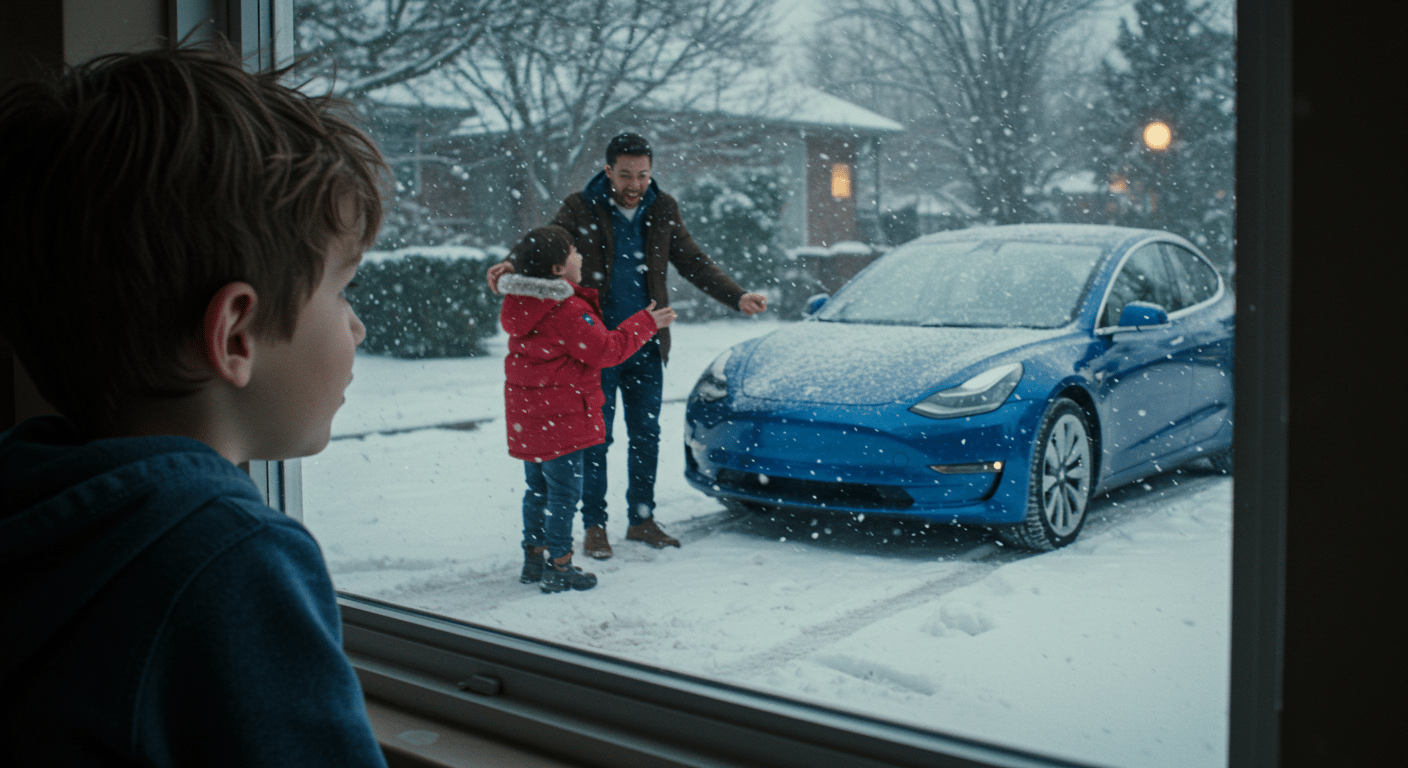

The desire to buy what we couldn't have as kids is a surprisingly common phenomenon. Psychologists even have a name for it: "compensatory consumption." It’s an act driven by a subconscious need to fill a void from the past. For my cousins, that trip to Disneyland wasn't just a vacation; it was the final chapter in a story they started writing as kids. And for me, it's about cars. I grew up in a nice neighborhood, but our family's cars were always old and reliable, never new or shiny. While other parents arrived in sleek, modern vehicles, my quiet embarrassment was a constant companion. That feeling of pulling into the school parking lot early, just to avoid being seen, is a memory that never quite fades. My desire for a nice car isn't just about the vehicle itself; it’s a way to rewrite that old memory—a visible statement that the once embarrassed boy has grown up and taken control of his own story.

This isn't just a personal quirk, either. The entire industry of "nostalgia marketing" is built on this very idea. Brands understand that a product which reminds you of a simpler, happier time—a retro video game console or a snack from your youth—is more than an object. It's an emotional artifact, a tangible link to a feeling. In a world that often feels complex and uncertain, these items offer comfort and stability. They are echoes of a more innocent time, and in buying them, we’re not just making a purchase; we’re recapturing a piece of that feeling.

Ultimately, the act of buying what we once dreamed of isn't a flaw in our character; it’s a fundamental part of being human. Our adult selves are, in a way, defined by the desires we held as children. The things we acquire later in life are often the pieces we need to complete our own narrative. It’s a way of saying, "I am no longer that person who couldn't have this. I am the person who made it happen." It’s a powerful statement of self-determination, a way of writing our own history, one purchase at a time.